Life Into Lines: John Elizabeth Stintzi in Conversation with Patrick Grace

John Elizabeth Stintzi, whose poem "Hale-Bopp" appears in the Malahat Review's Winter 2018 Queer Perspectives Issue, discusses their time living in Jersey, jumping between fiction and poetry, and writing about their gender journey in their Q&A with Malahat Review volunteer and past Publicity Manager Patrick Grace.

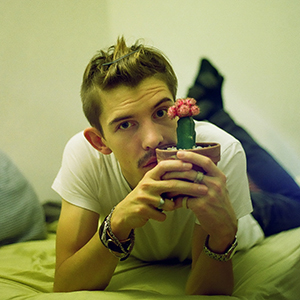

John Elizabeth Stintzi is a non-binary writer who was raised on a cattle farm in northwestern Ontario. A selection of their work has been published in Black Warrior Review, The Puritan, PRISM International, and their poetry chapbook The Machete Tourist (knife | fork | book, 2018). Also, in 2020 their novella The Rat King Scattered will be published by Ploughshares as a part of their Solos series. John currently lives in Kansas City with their partner, where they are currently at work finding a home for their first novel as well as their first collection of poetry.

Before we get into specifics about your poem, "Hale-Bopp," published in The Malahat Review's Queer Perspectives issue, I wanted to talk about your other literary successes. You recently published a chapbook, The Machete Tourist, with knife | fork | book, and in 2020, you'll be publishing a novella with Ploughshares as part of their Solos series. That's a good mix of poetry and prose. Would you say you're more inclined to write poetry or fiction?

It really depends what I’m feeling, dwelling on, living, and reading. Since graduating from my MFA in 2017 I’ve been focusing a lot of my time on fiction, since my thesis was a novel, and I thought “well, I should make this a better novel so I can sell it.” But now and again I get weary of fiction, or I need to let a novel or a story sit for a while, and suddenly I’ll find myself reading poetry and reflecting and life will fall into lines. My fiction is rarely explicitly autobiographical, so poetry is where I try to piece my lived experience together. I think poetry fits framing my life best because I often think my life is boring, and poetry is more interested in how you communicate it, in the language, rather than the experience itself. Also, I have so many more fiction projects than poetry projects (so many!) so writing fiction more is my way of trying to catch up with my brain. Poetry tends to sneak up on me, when I’m feeling things I need to work through, and I love that about poetry.

Your poem, “Confronting Wyrd at Poets House, NYC” in The Machete Tourist, is a great example of your oscillation between poetry and fiction, with lines like “I’ve done all that I can to kill poetry” and “To be a novelist, a novelist, a novelist now.” Would you banish writing poetry if you could? Why isn’t your fiction usually autobiographical?

Ha! That poem is a great characterization of what it can feel like to suddenly be bowled over by poetry. I would definitely never banish poetry, though, because if I did my fiction would certainly suffer. I feel like they cover different expressions. Poetry can be smaller—it's often just about me—and fiction is an expansion. It's me, it's my ideas, without the limitations of just being me. My fiction is way more autobiographical than I betray, only on a deeper, emotional and philosophical level. My novel, for instance, is about a non-binary photographer who is in their 40s when they return to their hometown of Winnipeg to see their mother—who they haven't seen since they ran away at 17—who has dementia and has just lost her capacity of speech. It's hard to look at that and think, "This is probably what John’s life looks like," but you might be surprised. My poem "Hale-Bopp," on the other hand, has nowhere to hide. All my work is related, of course. The poetry I write often gives me a sense of what questions I have, which I explore further in fiction.

Yes, let’s talk about the poem. In “Hale-Bopp,” the narrator finds comfort in a cactus during a time of isolation. Why is this the narrator’s “time of dying,” and why is this their “horror room”?

“The time of my dying" was referring to the deep isolation that I—the "speaker"—was going through at the time, when I was questioning and finally coming to terms with my non-binary identity. Specifically when I realized that I'd reached a point in my questioning where I concluded—most broadly—that I didn't fit within the binary, when I reached this point where I’d realized this true thing about me and could no longer slip back into believing otherwise. Which is pretty overwhelming. There are several evocations "dying" could carry here, but in a literal sense my "suicidality"—a term my therapist used—was at a pretty high watermark. The "horror room" is really just the specific and acute isolation of that little bedroom in Jersey, a recurring setting to many of the poems in my manuscript. Which was never quite the same after Hale-Bopp.

How did taking care of a cactus help you with this realization? Why did you name it after a comet?

Well, all succulents are inherently queer...but seriously, having Hale-Bopp mostly helped me practice they/them pronouns. Alongside them was when I first started to use them for myself. I think there was also something to living with a strange cactus who I didn't gender that felt like community. I already identified with their peculiarity and prickliness, so how could I not identify with the queerness I’d foisted on them? For the name, I named them after a comet because comets have the best sounding names. My first cactus was named Tempel-Tuttle, Hale-Bopp was my second, and now I have this wild coral cactus named Swift-Tuttle. Who is also queer.

I like the hyphenated names! In the poem, you mention a girl on Long Island that you’ve fallen for. How did this interrupt your flow with the cactus? I can’t help but think of The Little Prince, where the rose is jealous because the boy wants to explore outside of his world! Of course this poem is nothing like that, but I imagine a jealous cactus vying for all of your attention.

The best thing about a cactus is that they don’t really require much care. Which meant I could stay on Long Island as much as a week or more if I wanted to and wouldn’t really have to worry. I also like the idea of a jealous cactus vying for attention, but I don’t imagine Hale-Bopp that way. Being away from Hale-Bopp mostly just gave me perspective in my returning, when I’d check on them as soon as I got back, always happy to find them as ugly-cute and prickly as I left them. They were the main thing that made that place in Jersey feel at all like home, so when they died (when my space heater died while I was away in February, because our breaker was temperamental) I lost that small sense of home I’d been clinging to.

Did you find a new home after that? Your poem mentions leaving; that it’s what you needed to do, and that you were in a place no longer for you. Talk a bit how this death birthed a different path for you.

Yes, in the poem I write “Hale-Bopp was the symbol of the roughest arc / of my life, and their leaving told me nothing / except that leaving was what I needed to do.” With them gone, any illusions of Jersey having the possibilities of home were gone. Their death felt like the last straw in a box of last straws, by which I mean I’d turned their death into a symbol for why I should stop kidding myself. Why I should leave. But they were probably always a symbol. They only existed—in the ways they exist in the poem—with me there, making meaning of them. After them, my apartment was just a tiny bedroom with no ventilation and thin walls and garbage electricity and droopy floors that I paid way too much money for. The small, warm piece of poetic whimsy in the place was gone. The illusion that I had any community in that place shattered under that same flat stone. In many ways, I’m not sure I’ve found a home anywhere since, besides my relationship and my work. And more and more in my skin.

Does the theme of searching for a home come up in The Machete Tourist poems? For the readers who aren’t familiar with your chapbook, can you talk a little of the poems inside it?

I wouldn’t say The Machete Tourist is much about this search for home. Most of the poems climax my discomfort in my body, which does eventually inspire a search for the language to feel like home in that body. In its contradictions and confusions. There are also poems about love and human connection—I allowed myself to be a little eclectic with the chapbook, adding poems that I adore but know won’t make it to the first book—but I do think that the final poem “War Wounds” is the start of that search for a new way of being in the book. The search that poems like “Hale-Bopp” continue.

Will you continue that search for the self in future works? Can you talk about anything you’re working on now, or anything that you’re reading that’s getting more literary ideas bubbling?

I write about grappling with identity a lot, especially how a person lives with their choices. Having written this poetry collection, I’m much less interested in writing about my gender journey, but I do have a book of nonfiction loosely planned that will inspect other aspects of my identity (a project very far on the horizon). Right now, though, my main project is my second novel, which—like aforementioned first novel—is tied up in memory and identity and the act of interrogating one’s actions. It’s actually part of a larger project (I won’t call it a “series”) which includes the first novel as well as (at least) a third novel-in-progress. But we’ll see what happens. I’m really excited about the possibilities of it, but I’m also worried it’s going to blow up in my face. That nobody will care, that one or the other or the third book will be deemed unpublishable. But I believe deeply in it, and I hope my conviction is enough to keep my head down and not let the rejections distract me from believing this is a worthwhile endeavor. This said, between you and me, I have this silly belief that 2019 will be my year.

Patrick Grace

* * * * * * * *