St. Ann's Academy was at the centre of an industry in transition in Victoria. Over the course of the building's construction the practice of architecture changed from a mere part of the work of contractors, which was fairly wide open, to a controlled and singular practice for professionals. However, St. Ann's also reveals the continuity of older industry realities after the process of professionalization of architecture was complete in Victoria.

When Joseph Michaud built St. Andrew's Cathedral in 1858, he was not an architect in the same way that Hooper was an architect fifty-two years later. Michaud did not have formal training, and he built a fairly simple church, which he embellished with his impressive skills as a carpenter. The 1860 Victoria Directory listed Michaud simply as a frere, and he probably considered building as only a small part of his work as a Catholic brother.1 Charles Verheyden was among the first architects in BC, but he advertised himself as a builder, contractor, and carpenter.2 He commanded a worthy fee for his work for the Sisters of St. Ann, but he had almost no influence on the design of the building.3 Teague, too, was an engineer who taught himself architecture without any overarching interests in style or theory, though he did start to exhibit his own emerging architectural tastes in his work. Hooper, on the other hand, was a career architect with practices from Victoria to New York, and he was very interested in prevailing trends and stylistic concerns.4

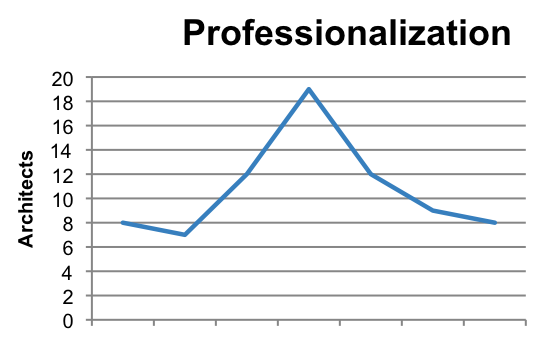

The number of individuals in the Victoria City Directories listed as architects increased rapidly in the 1880s and early 1890s, but it fell off dramatically after 1895. The drop occurred during a period of economic prosperity for construction in BC, so the drop illustrates the emergence of architecture as an elite profession in Victoria. The industry experienced immense growth, but the number of practitioners fell because a smaller number of participants chose to work exclusively as architects and they separated themselves from contractors and builders, who would formerly have operated as architects.5

The development of new titles for work was one of the most important symptoms of professionalization, and The directories of BC reveal that individuals increasingly identified themselves as "architects," rather than "carpenters," "contractors," or "builders."6 During the late nineteenth-century, the status of architecture in British Columbia changed dramatically, and architects ascended in practice and status from laborers to businessmen of a respectable profession. This was clear in the fact that Teague, an architect, became mayor on his reputation as a clear-headed businessman in 1895.

Despite the growth in status, architecture in BC was still a practice predicated securely on work. Teague along with Hooper grew rich not on grand public buildings like St. Ann's but on the dozens of repetitive commercial buildings they built on Government Street, Johnson Street, Yates Street, and Wharf Street, in Victoria's booming downtown commercial district. Samuel McClure was the only rivals to Francis Rattenbury as BC's most popular Architect at the turn of the century, but he still built a modest brick laundry for St. Ann's at the height of his career. Architects chose to associate themselves more with their grandest works, but their success still relied on hard-work and shrewd business sense in a competitive market.7

Non-professionals also continued to practice architecture into the twentieth century. Sister Mary Osithe, the St. Ann's art teacher, constructed several buildings around BC including the St. Ann's gymnasium in 1922. Like Michaud before her, Osithe would not have imagined her work as an architect anything like Teague or Hooper did, since designing buildings was one of her duties to her religious order. Osithe never competed with the professional architects for commissions, and her addition to St. Ann's reveals the existence of architects in an older sense of the practice operating outside of professionalism but still making important contributions to British Columbia.

The architects of St. Ann's operated within and around the changing nature of architectural practice, and they reveal a contested professionalization of architecture in Victoria.

Footnotes

1 BCA, Victoria City Directory, 1860.

2 BCA, Victoria City Directory, 1868.

3 Hallmark, "St. Ann's Chronology 3rd Edition," 1986.

4 Donald Luxton, "Thomas Hooper, 1857-1935," Building the West: the Early Architects of British Columbia, Donald Luxton, ed. (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2003), 140.

5 BCA, Victoria City Directories. And G.E. Mills, Architectural Trends in Victoria, British Columbia, 1850-1914, Manuscript Report Number 354, (Parks Canada, 1976), 22.

6 BCA, Victoria City Directories. And Burton J. Bledstein, The Culture of Professionalism: the Middle Class and the Development of Higher Education in America (New York: W.W. Norton, 1976), 4-5, 6, 34, 37, 38.

7 BCA, Verticle Files, Thomas Hooper, "Former Victoria Architect Dies." Colonist. 8 Jan 1935. And BCA, Verticle Files, Thomas Hooper, "Thomas Hooper Returns on Visit." Colonist. 8 Mar 1927.

Photos:

BCA, "The Anton Henderson Home on Rupert Street, Victoria," c.1890, B-04908.

BCA, Thomas Hooper "Architect Thomas Hooper's proposed Methodist Church, Pandora Avenue," c.1890, H-03168.

Thomas Hooper, Architect: Victoria & Vancouver BC, AD MCMX, Vancouver: Evans & Hastings, 1910, NW720.9711 H788t.