Reviews

Nonfiction Review by L. Chris Fox

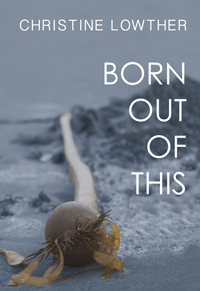

Christine Lowther, Born Out of This (Half Moon Bay, B.C.: Caitlin, 2014). Paperbound, 208 pp., $21.95.

Last December, when Christine Lowther read at Victoria’s new reading series at the  Fairfield Market, she read from Floating, Asphalt, and Merge, the three sections that make up her memoir, Born Out of This. I particularly appreciated Floating, which is as long as the other two sections combined. Its second (and longest) essay, “Gifts from Lands So Far Apart,” gently, deftly, introduces readers to the loss of her mother, notable B. C. poet, Pat Lowther, at the hands of her father. Remarkably, the trauma, anger, and grief that event precipitated has been transformed by Lowther into the activism and the impressive attentiveness that inform both her writing and her life. Although it touches on a diverse number of subjects (ranging from bioluminescence to punk to gardening to visiting squats in London), Born Out of This has a discernible narrative arc that traces Christine Lowther’s unique responses to “trauma, bravery, resilience, the long road of recovery, grief.”

Fairfield Market, she read from Floating, Asphalt, and Merge, the three sections that make up her memoir, Born Out of This. I particularly appreciated Floating, which is as long as the other two sections combined. Its second (and longest) essay, “Gifts from Lands So Far Apart,” gently, deftly, introduces readers to the loss of her mother, notable B. C. poet, Pat Lowther, at the hands of her father. Remarkably, the trauma, anger, and grief that event precipitated has been transformed by Lowther into the activism and the impressive attentiveness that inform both her writing and her life. Although it touches on a diverse number of subjects (ranging from bioluminescence to punk to gardening to visiting squats in London), Born Out of This has a discernible narrative arc that traces Christine Lowther’s unique responses to “trauma, bravery, resilience, the long road of recovery, grief.”

A short essay, “The Spawning Grounds,” where the adult Lowther sets out to harvest dead chum salmon for her floating greenhouse garden, opens the collection and metaphorically sets the stage for Lowther’s creative journey. In “Gifts,” Lowther steps back in time to introduce her mother’s poems and activism, threads she employs to weave and write her own life. She describes the family’s summer trips to Mayne Island, “the first place to imprint itself onto [her] heart”; the view of Bennett Bay from Bill Wilk’s Sleepy Hollow cabin: “small, round, forest-cloaked islands squatted on the water like shaggy mushroom caps.” Full disclosure: I know that view; I rented one of the “unfamiliar single-room rental cabin[s] across the road” to which Lowther’s father takes the children, Christine and her sister Beth, who do not yet know that he killed their mother.

Pat Lowther’s poetry and the prelapsarian beauty of Mayne are the matrix that will, over time, heal the child, who is “never again to be touched by either parent, the child [who] knows she’s still alive when solid ground embraces her”; the child who will eventually “emerge from the ocean…reborn.” For Christine Lowther seems to find in nature the mother she lost, a healing, comforting companion that, in the end, becomes herself and her own poetic gift. For make no mistake, though these personal mini-essays are called prose, still they are infused by the poetic: a “seal’s smooth back curves above the water”; “Orion’s belt slips one star at a time behind the tree line.”

Although Asphalt is the shortest section, it speaks strongest to the political aspect of Lowther’s memoir. Here she invokes the wild in the city (from punk to racoons), communal urban gardens, and “Generally Giving a Damn.” Lowther explains the pull of punk; how she was “drawn to the political consciousness, the freedom to express anger and demand justice; the ecstasy; the trust when leaping from a stage; the insistent questioning and remaking.” In the third section, Merge, Lowther brings together her grief for her mother with her grief for the B. C. wilderness, for the planet; joins her rural, solitary self to her urban dancer; merges politics and poetics.

Born Out of This has an air of mixed genre about it because it includes more poetry than is usual in a collection of essays, but also because it is part memoir, part call to arms, both ecological and artistic, part a plea for détente between urban and rural. It can even be read as a brief introduction to the poetics of Pat and Christine Lowther or as a brief history of ecological battles of the West Coast, many of which are listed in Postscript, while Lowther describes her own direct actions protecting the Walbran Valley and a Tofino tree named Eik in earlier essays. Predominantly, however, Born Out of This is a love letter to Clayoquot Sound. Lowther’s love of detail and nature is apparent in her description of winter huckleberries in the woods: “their black and maroon aura, small, very firm and not too sweet, but cold and juicy with a satisfying chewy texture.” However, her love is not apolitical, as she chews she’s reminded of Briony Penn, who eats local fruit “instead of the fruit of yet another banana republic.” Perhaps nature became the mother she could defend successfully. Yet, when “pure beauty wakes [her] in the morning,” I am reminded of Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. In fact, in the latter half of Born, Lowther invokes many celebrated West Coast “nature” writers. Moreover, the fact that Tim Lilburn, Don McKay, Jan Zwicky, Maleea Acker, and Briony Penn are credited in footnotes adds an academic air to the collection, although, unfortunately, there is no final bibliographical listing. That Lowther touches on all this in a mere 200 pages is a remarkable feat. Less successful are the photographs; not because Lowther’s photographs aren’t good (they are!), but because the size and lack of colour are inadequate to their subjects. Here, perhaps, fewer photographs, more richly displayed, would have been more effective. However, this may be where the parlous state of the small press in Canada trumped aesthetic desire. It is more than enough that Caitin Press has allowed Lowther’s lovely slim volume to be Born Out of This.

—L. Chris Fox